Maybe you’re from the West and managing a Filipino freelancer, remote team, or local team. Perhaps you’re traveling to the Philippines or living here as an expatriate for whatever reason. A few things to consider when working with Filipinos.

Same Same, but Different

Filipino culture is a nuanced, multilayered iceberg that lurks under the oddly familiar facade of Americana. This manifests in hip-hop culture, slang, fast food outlets, convenience stores, relentless social networking, and an aspirational middle-class, among other things.

The writer Carmen Guerrero Nakpil neatly summarized American culture spread across the surface of Spanish colonial residue with “Filipinos have lived 300 years in a convent and 50 years in Hollywood.”

Today, there is a Gibsonean syncretism to Pinoy culture. It’s layering on new influences as Asian dynamism throws cultural manifestations like K-Pop, Tik-Tok, Pinoy cinema, Chinese hegemonic flexing, and Anime into the firmament. These influences are accreting on the Philippines’ rambunctious history: American expansionism on top of Spanish rule administered by Catholic zealots in the north and the central parts of the country, Muslim sultanates in the south, and animist tribes in the mountains.

Philippines History Layering, an Illustrative Example

In the dim mists of precolonial history, ethnic Malays strained at their paddles in outrigger canoes called balangays. They navigated the nuances of current, stars, and magic to arrive at what would later become the Philippines.

The word balangay became barangay.

Today, we know barangays as the Philippines’ basic socio-political unit. The Spanish adopted the word and coopted the barangay structure through resettlement programs called the reducción. They installed loyal leaders to collect taxes and enforce Spanish edicts. (Conceivably, today’s political dynasties trace their lineage back to these leaders.)

When the Americans arrived, barangay slid to barrio as they reworked the local government units to suit their colonial objectives. In the 70s, a local mayor reorganized the barrio structure into a barangay system template. Ferdinand Marcos appropriated the system and, through fiat, rerechristening barrios as barangays in 1974. He then incorporated the concept of baranganic democracy into his New Society program to affirm his political position.

Pinoy Culture is Seriously Tribal

The Philippines lies somewhere between the clean lines of Japan and China’s purist culture and the omnivorousness and fragmentation of American culture.

The term “tribal” connotes thoughts of rituals unavailable to outsiders and kinship structures that manifest in relationships and mutual responsibilities.

The American take on tribal relationships is that they are elective, whereas Filipinos view tribal relations as pre-ordained — nearly divine in their mandate. The tribe is, upon closer inspection, strictly hierarchical, enigmatic, highly self-referential, and, above all, derived from the family.

The Filipino Family Rules

If there is one thing that overrides any other value, it’s family. Filipino families are sprawling in size (usually) and compactly domiciled, and it is the fundamental tribal unit and the foundation for all social interaction.

Wealthy Filipinos often congregate in family compounds, and the less affluent cluster on communal land plots or inhabit the same neighborhood. Family dynasties rule politics, and family businesses are the norm.

Family obligations are compulsory and usually trump any other consideration.

A job will never take precedence over family, and the rationale for a Filipino’s job will likely be to honor familial duties and responsibilities. Filipinos routinely leave home for their entire professional career, opting to work abroad on behalf of and painfully separated from their family to provide for their family.

One term you routinely hear uttered with a hush of respect: breadwinner. This person will support any number of relatives. This can include as many as ten family members on a single call center agent’s salary, often sacrificing their health and well-being.

Everyone has a prescribed role in the family, and the relationships with the family are well-defined and organize the Philippines’ collective worldview.

Family relationships are, in a sense, the template for both economic and political relationships. This is well worth remembering since the ability to organize familial-like relationships with your employees, customers, and suppliers determines your success.

Pakikisama & Pakikipagkapwa (Smooth Sailing)

Filipinos prize smooth interpersonal relations seeking harmony and personal dignity.

The term pakikisama in Tagalog refers to being able to get along, and it describes togetherness and camaraderie as well as civility. One way to look at pakikisama is the desire for social acceptance manifested through loyalty.

In a business context, pakikisama encourages employees to work for the group’s common good and can be a robust support system. Its disadvantage is that loyalty rather than objective analysis may influence decision-making.

Pakikipagkapwa is pakikisama in action, where people prevent conflict at almost all costs. This can work well in many situations, but avoiding conflict at all costs may yield unintended consequences.

In this context, communication is as much about smooth, comfortable interaction as description, especially when the answer may be unpalatable. This is where the profusion of “yeses” and “maybes” occurs. A Filipino rarely says “no.” You must look behind the spoken language to recognize subtle queues and inflections that belie dissonance to see the actual reply.

The Intermediary

When you need a definitive resolution, a go-between — someone esteemed by both parties — smooths communication for uncomfortable topics. In a work setting, it’s essential to feel comfortable with this intermediary (usually a manager or supervisor) and calibrate for clarity.

Utang na Loob (Strings Attached)

Within the framework of tranquil community relations and cooperation lies utang na loob, or debt of gratitude. Utang na loob describes a debt incurred when one person takes care of another.

Covering for a colleague, recommending someone for a promotion, or shouldering an employee’s medical bills all qualify as overt acts that render a debt of gratitude. Like many things that work deep in the cultural operating system, these reciprocal relationships can occur overtly or quite subtly.

It’s important to understand that big asks create onerous obligations, particularly as a foreigner in the Philippines.

None of this is discussed because the debt is apparent and implicitly understood from the Filipino perspective. Unknowingly incurring an obligation can create unexpected challenges since you are expected to render payment, and that discussion will likewise be handled as a fait accompli.

Hiya & Amor-propio (the Regulators)

If you’ve encountered reticence amongst your team or during your travels around the Philippines, you’ve seen hiya at work. Many pundits use the term “shame” to describe hiya, but I think it’s more of a reluctance to do something that might cause shame.

A subordinate mindful of publically displaying ignorance may retreat from clarifying procedures, even if ignorance has significant consequences. Moreover, hiya creates a taboo around public disagreement and criticism.

Western managers regard public coaching and generative discord as benign — a way to enlighten the whole team efficiently. In general, Filipinos regard this as persecution where you have singled someone out and challenged their position in the group.

Conflict ensues after a person’s self-respect, or amor propio erodes beyond the capacity of the offended party to endure the perceived injury. These dramas play out in a public setting, real or imagined. Civility exits when personal honor is at stake, and the group dynamic resets.

You may, quite unintentionally, violate an employee or acquaintance’s dignity because the boundaries can be opaque. Personal quirks and cultural predispositions rule these unmarked frontiers.

Bahala Na

Bahala Na means “Leave it to God” and describes a stoic perspective on matters large and small. This also provides a mantra for persistence in the face of the many challenges life serves up daily.

Colonized by Spain and turned into a theocratic state, subjugated by nascent American imperial ambitions, brutalized under Japanese occupation, oppressed by political corruption and entrenched oligarchs, and beset by natural disasters; you might forgive Pinoy culture’s auto-immune reaction of a sort of bemused acceptance.

Resilience & Resourcefulness

Alluded to above, and perhaps derived from their deep faith, Filipinos are resilient, capable of tackling challenges and setbacks with grit and perseverance.

Filipinos are well known for their positive outlook on life, perhaps one of their most definitive traits. Despite the challenges they face, Filipinos always seem to find a reason to smile.

This is also evident in their ability to make do with what they have on hand. This resourcefulness is indicative of the Filipino people’s can-do attitude.

When the US Military departed the Philippines after WWII, they left thousands of Jeeps behind. Filipinos quickly put these to good use, using them as taxis, buses, and even ambulances and localizing the name with the diminutive Jeepney.

Jeepneys are living monuments to improvisation, and while their utility has waned in recent years, they remain emblematic of the Philippines.

Bayanihan (Many Hands)

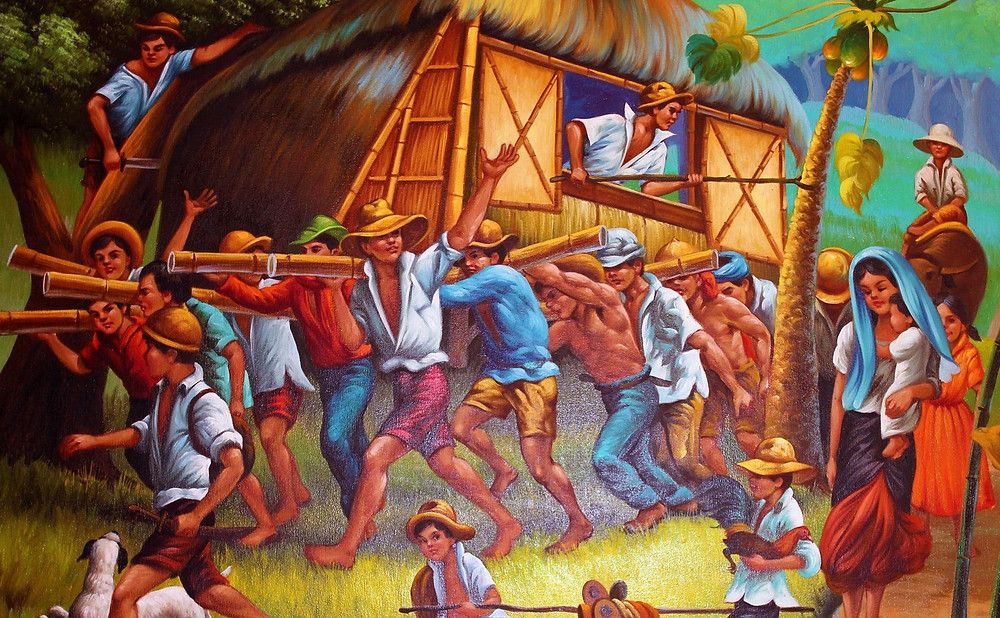

Group resilience materializes whenever natural disasters hit and, most recently, during the pandemic and its response. If you search bayanihan, most posts will include some rendition of the image below, a village moving a nipa hut — the collective at work.

This is the bayanihan, or community spirit, where group bands together to perform a selfless act. It stands in stark contrast to utang na loob, where patronage between two individuals gets the job done. This energy operates in the light of day, and it is a strong motivator for the timeless gesture of helping your neighbor, colleague, or community.

Hospitality

Anthony Bourdain summed up Filipino hospitality with this statement: “Filipinos are, for reasons I have yet to figure out, probably the most giving of all the people on the planet.”

This trait is evident in everything from how Filipinos welcome guests into their homes to how they care for extended family members. It’s not uncommon for Filipinos to offer their guests food and drink, even if they’ve just met. This hospitality isn’t limited to friends and family but extended to strangers.

On Chimeras and Stereotypes

On the one hand, there is the Philippines colonized by Spain for 400 years and then governed by the US for 50 years. This colonial experience has bequeathed a society with many Western characteristics: Roman Catholicism, Spanish, and English as official languages, the use of surnames, a strong work ethic, and an appreciation for education.

On the other hand, there is the Philippines which the West never colonized.

This experience has resulted in a society with Asian characteristics: a focus on extended family networks, a preference for consensus decision-making, a more relaxed pace of life, and a spiritual rather than materialistic outlook.

Ultimately, I could cite dozens of examples that contradict each of the above traits. I’m left with Pallavi Aiyar’s comment in her recent Nikkei Asia Same, same but different: curse of the stereotype as she describes how utterly crude and unsatisfying it is to try and explain national identity.

As an “explainer” of places one must always calibrate the proportion of detail, truthfulness, boosterism and sheer laziness that comprise all explanations. Stereotypes play to the black and white tones in which we all seem wired to see the world, even though it is bathed in shades of gray.